Main Content

Fields of work of Semitic Studies

Ethiopian Studies

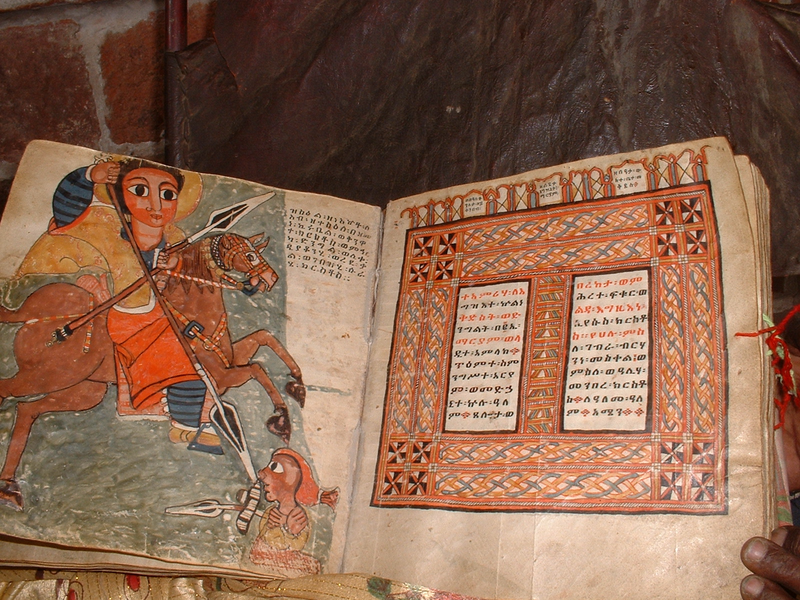

Ethiopian Studies is a branch of Semitic Studies on the Semitic languages spoken in Ethiopia and Eritrea, as well as the archaeology, culture, history, and religion of this area. In Marburg, the focus of Ethiopian Studies is on studying and teaching Gǝʿǝz (ancient Ethiopian). The earliest epigraphic references of Gǝʿǝz date from the 3rd Millennium AD and were first written in an unvocalized script, which later, in the 4th Millennium, was modified by diacritic characters to become syllabic writing. Gǝʿǝz was the central language of the Kingdom of Aksum, which extended as a great power over the ancient world of Northern Ethiopia, Eritrea and, for some time, over parts of Sudan and Southern Arabia. As early as 370 AD, the Ethiopian king Ezana converted to Christianity, making Ethiopia one of the oldest Christian countries in the world.

During the 13th Century, the origin of the national epic Kǝbrä Nägäst, “Glory of the King”, was one of the most beautiful and important works of Ethiopian literature. Over time, Gǝʿǝz was replaced by Amharic as the language of communication, but it continued to be used in literature until the 19th Century and is still used today as the liturgical language of the Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Churches. Today, Amharic is the second largest Semitic language and is the administrative language of Ethiopia. It has a very extensive and linguistically sophisticated body of literature.

Arabic Studies

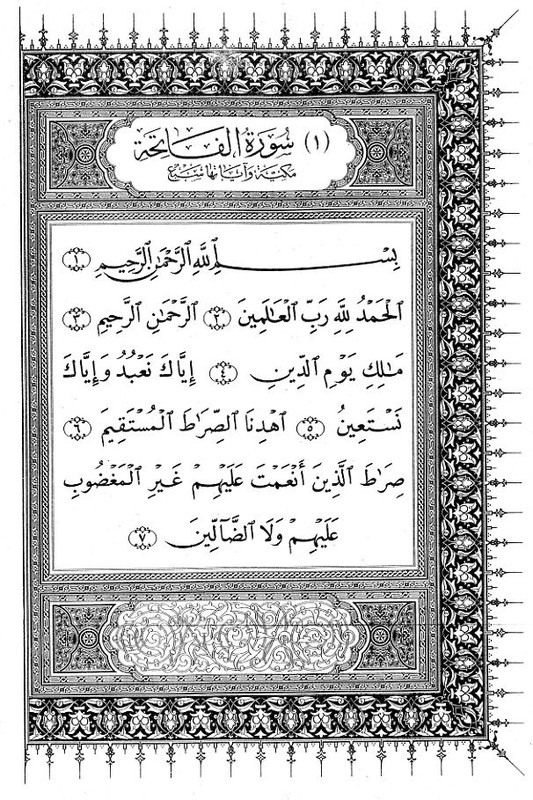

The focus of study for Arabic Studies within the discipline of Semitic Studies is on classical Arabic, Middle Arabic and Arabic dialects of the present day. Classical Arabic focuses on the language of pre-Islamic poetry, the Quran and historical and legal writings. As Islam advanced, Arabic replaced native languages as a cultural language. The systematic translations of scientific and philosophical works, mainly of Greek but also of Syriac, Pahlavi, and Sanskrit between the 8th and 11th Centuries AD, also made Arabic a more scientific language in the area of the Near and Middle East. Scientific texts in particular are the subject of a lot of research in Semitic Studies at Marburg. Directly derived from Classical Arabic, Modern High Arabic is an official language in 18 countries today. Modern High Arabic is mainly used as a written language, a language of the media, and for official purposes.

Arabic dialects are used in addition to High Arabic as an everyday communicative language in all Arab countries. Unlike Modern High Arabic, which is the same in all countries, Arabic dialects differ considerably from place to place. An essential feature of Arabic, from the earliest period to the present day, is its diglossia. Diglossia means that two linguistic forms of Arabic are used simultaneously – a standardized form used as a written language and in formal communications, and a second form used as a common language. The term Middle Arabic doesn’t refer to a language level, but rather is a sociolinguistic construct. Middle Arabic is a mixture of forms from colloquial and Classical Arabic. Another feature of Middle Arabic is its use of other scriptures such as Syriac or Hebrew.

Aramaic Studies

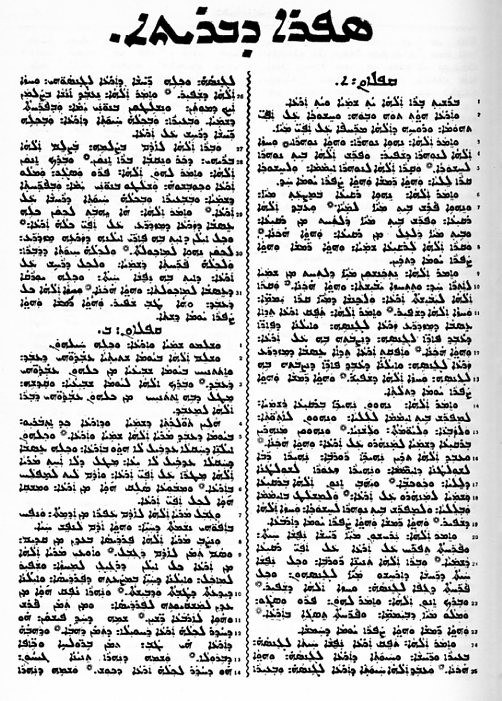

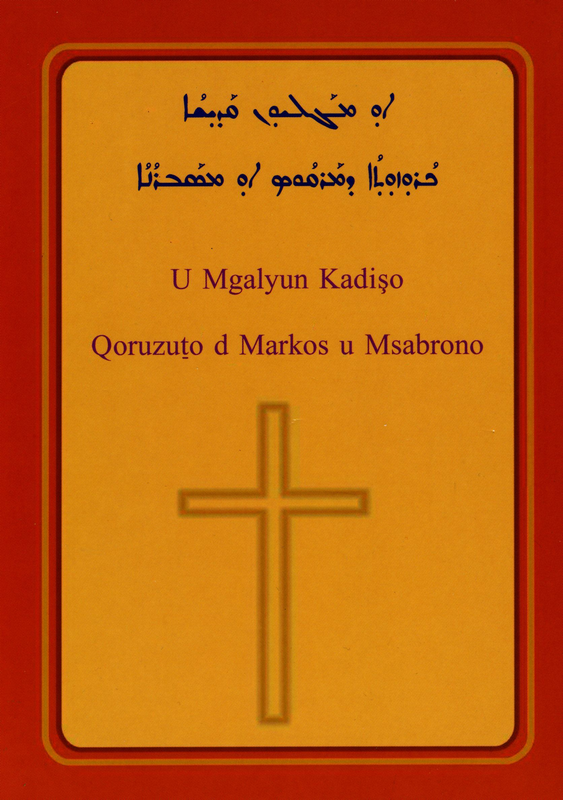

Aramaic Studies focuses on the various varieties of the Aramaic language, from the 10th Century BC to the present day. In Marburg, research is being conducted on both the older varieties of Aramaic (Imperial Aramaic, Syrian) as well as modern Aramaic (Turoyo). The oldest surviving language level is Ancient Aramaic, used in legal and administrative documents from the Assyrian Empire in the 7th Century BC. This was followed by “(Achaemenid) Imperial Aramaic” - a form of the Aramaic language used in the Achaemenid Empire (6th – 4th Century BC) as an administrative language. Imperial Aramaic also appears in some passages of the Old Testament as “Biblical Aramaic”. From around the 3rd Century BC, Ancient Aramaic became Middle Aramaic, and the existing division between Eastern and Western Aramaic was strengthened. Since Aramaic had replaced Hebrew as the everyday language of the Jewish people, the various dialects of Middle Aramaic were also used in written languages, such as Targumim, and therefore the Aramaic translations of the Old Testament. This also meant that Aramaic became an important Jewish literary language. The most important variety of Middle Aramaic for Christianity is Syriac. This Aramaic dialect from the city of Edessa (today Şanlıurfa in Turkey) became the literary language of Christianity in particular through the Peshitta, the Syriac translation of the Bible. Today it is still used in the liturgy of various churches in the Middle East. In addition to the Peshitta, many other works in the fields of theology, philosophy, historiography, and poetry were written during the prime of Syriac. The Eastern dialects of Middle Aramaic include Syriac, Judaic-Babylonian-Aramaic, and Mandaic. The Western dialects of Middle Aramaic, on the other hand, include Judaic-Palestinian-Aramaic, Christian-Palestinian-Aramaic, and Samaritan-Aramaic.

After the Arab Expansion, Aramaic gradually lost its importance as an everyday language. However, there are still hundreds of thousands of speakers of the new Aramaic languages, mainly in Syria, Iraq, and southeastern Turkey. In addition, many speakers of new Aramaic live in diasporic communities. The new Aramaic languages include, among others, Northeastern-New-Aramaic, Turoyo, New-Mandian, and New-Western-Aramaic. The linguistic developments can be observed diachronically through the long traditions of three millennia, a characteristic of only a few other languages in the world. Above all, the verbal system of some varieties of New Aramaic completely transformed in comparison to older varieties. New Aramaic is also linguistically similar to neighboring languages such as Arabic, Turkish, and Kurdish, which impacts the vocabulary in particular, but also impacts the phonology, morphology, and syntax of new Aramaic. On the other hand, Aramaic as a substrate language influences Arabic, especially the dialects of the Levant.

Hebrew Studies

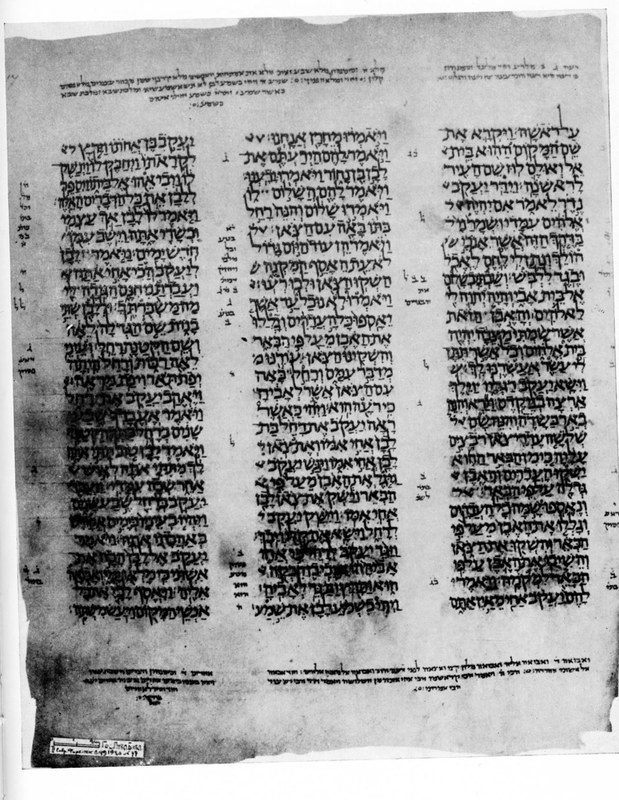

Hebrew Studies focuses on the three different language levels of Hebrew as well as the history, culture, and traditions of the Jewish people. The oldest level of Hebrew is called Old Hebrew, or Biblical Hebrew, which was used by the Israelites in Canaan in the 1st Millennium BC, for example in inscriptions. The most famous work in this language is the Old Testament. What’s more, the oldest surviving Bible manuscripts, the notable Qumran scrolls, were written in this language. The greatest achievement in understanding Biblical Hebrew is thanks to the scholars called ‘Masorets’, who provided the Bible, originally written only in consonants, with a system of vowels between the 7th and 9th Centuries BC. Mishnah-Hebrew is a literary language, which was used primarily to write religious texts. In around the 5th Century BC, Hebrew was gradually replaced by Aramaic as the everyday language, and was used only as a liturgical language and for formulating philosophical, medical, legal and poetic texts.

At the end of the 19th Century, attempts to revive Hebrew began. Modern Hebrew, the Ivrit, was the result of this revival and development. Today, Hebrew is the official language of Israel in addition to Arabic. The focus of Hebrew Studies in Marburg is on Biblical Hebrew and Modern Hebrew. Modern Hebrew language courses are offered by the Department of Semitic Studies at regular intervals. Biblical Hebrew is regularly taught by the Department of Evangelical Theology as part of the field of the Old Testament. Other courses are offered by the Department of Semitic Studies.

Sabaean Studies

Sabaean Studies focuses on the language, culture, history, and religion of the Kingdom of Saba, which existed in western Yemen from the beginning of the 1st Millennium BC until the end of the spread of Islam in the 7th Century BC. Archaeological remains preserved to this day are a testament to the prosperity of the Sabeans. These include the remains of the legendary Great Dam near the capital, Marib, which was the largest technical structure of the Ancient World. In addition to Sabaen, ancient languages of Yemen also included Mina, Qataban, and Hadramitic, of which Sabaean is the most well document and studied language. So far, around 6,000 inscriptions have been found on stone, bronze, and wooden sticks.