Main Content

Energy Materials

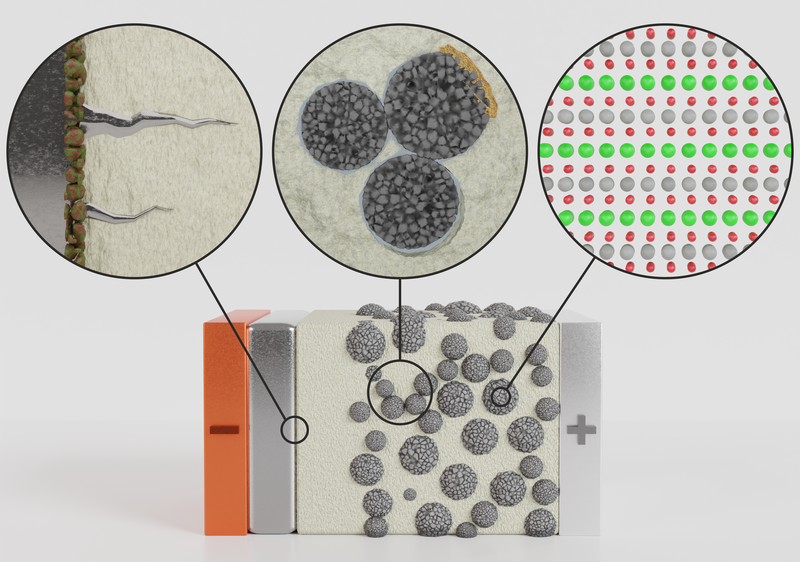

Solid-State Batteries

In our research group, we work on the batteries of the future that are intended to eventually replace conventional lithium-ion batteries. Solid-state batteries based on lithium or sodium are particularly promising, as they use a solid material instead of a liquid electrolyte. This enables the use of new anode materials, increasing the energy density compared to conventional lithium-ion batteries. In addition, safety is improved through the use of non-flammable materials and enhanced thermal stability. However, several challenges still need to be resolved before solid-state batteries can replace lithium-ion batteries. In particular, the interfaces between the solid electrolyte and the anode or cathode pose a problem, as unwanted phases can form there or the materials may delaminate, blocking ion transport. To avoid these issues, a fundamental understanding of the materials is required. We use our high-performance electron microscopes to investigate the chemical composition and structure of these materials down to the atomic scale. An example workflow for the investigation of battery materials can be seen in the video of the FestBatt project.

Fuel Cells

Green hydrogen will play a crucial role in the energy transition. To produce green hydrogen, we require electrolyzers, and to convert stored hydrogen back into electrical energy, we need fuel cells. In this field, we investigate proton-conducting solids that can be used as electrolytes in electrolyzers and fuel cells. More specifically, we study how dopant atoms influence the morphology and structure of these materials. In addition, we aim to further develop the method of momentum-resolved scanning transmission electron microscopy on these materials, in which the microscope’s electrons are deflected by electric fields within the material, allowing conclusions to be drawn about the internal electric fields of the sample.

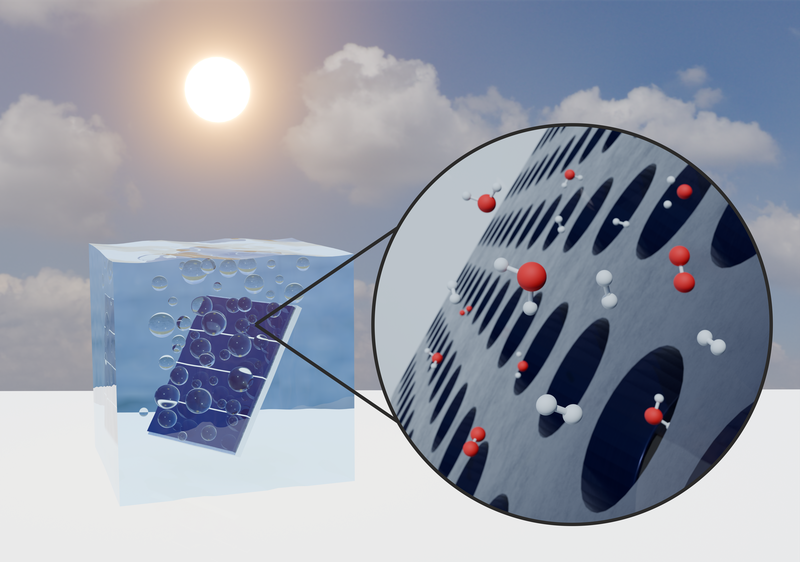

Solar Cells for Direct Water Splitting

Another approach to producing green hydrogen is direct water splitting using solar cells. For this purpose, so-called tandem solar cells—where two different solar cells are stacked on top of each other—are employed. These absorb different regions of the solar spectrum, increasing the overall voltage of the solar cell to more than 1.7 V, which is required to split water into oxygen and hydrogen. In this area, we aim to correlate degraded performance characteristics of the solar cells with structural defects in order to optimize the materials. As with the fuel cells, the method of momentum-resolved scanning transmission electron microscopy will also be used here to measure electric fields at the pn junctions of the solar cell.