Main Content

Research

The vast majority of people acquire their native language without problems and much effort. Acquisition proceeds in relatively organized stages and around puberty age most people have a good intuition about the grammatical rules of their language and have developed a substantial vocabulary. Nevertheless, individuals differ in their language skills.

There is variability within the same language user, such that – for example – two realizations of the same word are never identical but show subtle differences. When considering differences between individuals, it becomes apparent that there are massive individual differences in linguistic skills and non-linguistic skills involved in language processing. Some language users speak extremely fast, others rather slowly. Some have an elaborate vocabulary; others restrict themselves to a limited, possibly more specific set of words. In addition, language users often process non-standard variants of a language (i.e., dialects) or foreign-accented speech.

The high variability at all levels of linguistic representation (e.g., phonetic, phonologic, semantic, syntactic, pragmatic) poses challenges to the language production and comprehension systems. The junior research group investigates the origins and consequences of this variability.

Experimental techniques

Investigating a multifaceted object such as language requires a variety of different tools. In our research group, we mostly rely on experimental techniques from psycho- and neurolinguistics.

Behavioral research

Using behavioral techniques, we investigate participants’ linguistic and non-linguistic skills and the interactions between them. Behavioral experiments help us understand how different learning environments influence the retention of to-be-learned material and which factors have a facilitating or impeding effect on language comprehension and language production. One of our research lines examines the influence of different learning environments on the acquisition of novel linguistics representations. More information on this strand can be found here.

Furthermore, we often apply so-called individual-differences approaches, where large samples of participants are recruited and tested on a variety of tests. The participants' data from different behavioral and neurolinguistic tests are examined and compared. The goal of these studies is to examine how the performance on one task is related to the performance on another task and how the behavioral performance is related to or can be explained based on neuronal activity or eye movements. More information on one of our individual-differences research strand can be found here.

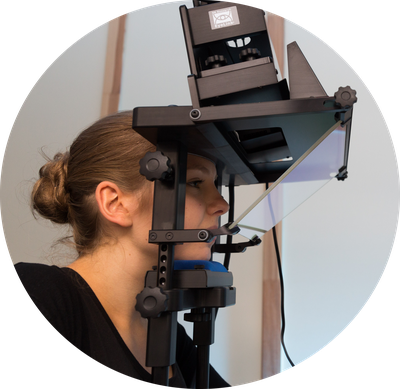

Eye-tracking

Language production and comprehension are extremely fast cognitive processes. We are able to process up to 300 words per minute such that the mechanisms underlying planning and comprehending language must occur within milliseconds. Eye movements are a helpful instrument for investigating these (subconscious) processes, which often occur before we are consciously aware of a stimulus. Eye-tracking can be used to capture movements (e.g., first fixation, fixation durations) or pupil dilations, which are related to changes in cognitive demands, with high temporal resolution. Eye-tracking can be used to examine comprehension processes of spoken and written language, to understand the integration of spoken language with visual input or to capture the cognitive processes that underly planning and execution in describing a visual scene.

Electroencephalography (EEG)

To investigate the neuronal activity underlying the processes involved in language production and comprehension, we rely on EEG measurements, which – as eye-tracking – have high temporal resolution. For example, EEG (i.e., electrical brain signals) of participants can be recorded when processing linguistic stimuli such as isolated words, sentences or gestures. Stimuli can be presented in the visual or the auditory modality, or in combination to look at the integration of multi-modal representations. If we are interested in the brain response to a specific stimulus, the neuronal activity is derived starting at the onset of the stimulus and is subsequently averaged over multiple similar trials in order to yield so-called event-related potentials (ERP). ERPs visualize the time course of neuronal activity in a predefined brain region and can be compared between participant groups and conditions. Using EEG, we gain insight into fine details of language processing that are not observable on a behavioral level.