Main Content

Conference „Responsibility to Protect and Humanitarian Interventions – Military Force in the Name of Human Rights?”

With the display of the video I declare that I consent to the data transfer to YouTube. Further information in the Data Protection Declaration .

With the display of the video I consent to the data transfer to YouTube. Data Protection Declaration .

6. to 8. November 2023 in Hannover

Henning de Vries (Marburg) | Stefanie Bock (Marburg) | Eckart Conze (Marburg) | Fabian Klose (Köln)

The International Centre for War Crimes Trials (ICWC), led by Prof. Dr. Stefanie Bock, Prof. Dr. Eckart Conze, and Managing Director Dr. Henning de Vries, together with the University of Cologne, represented by Prof. Dr. Fabian Klose, organized the symposium “Responsibility to Protect and Humanitarian Interventions – Military Force in the Name of Human Rights?” from November 6 to 8 in Hanover.

The Volkswagen Foundation supported the conference with over €40,000 as part of its thematic week on “Human Rights in Times of Multiple Challenges – Perspectives from Science and Society” and provided the conference venue at the conference center of Herrenhausen Palace.

With its symposium, the ICWC addressed the questions of to what extent states are obligated to protect their citizens from systematic violence and international crimes, and what role humanitarian interventions can play when this responsibility to protect (R2P) is not fulfilled. The discussions also examined how different responsibility regimes emerge in international law and whether these can be integrated into a concept of global responsibility.

The symposium was designed to be particularly interactive: in addition to keynote lectures and panel presentations, participants benefited from intensive professional exchanges, stimulated, for example, through a fishbowl discussion, a World Café, and a negative-positive conference.

Dr. Henning de Vries (Marburg) opened the symposium by explaining that the goal was to analyze and clarify the limits and transgressions of military force based on human rights, using the concepts of the responsibility to protect and humanitarian intervention. To this end, the thematic focus of the symposium was discussed along several aspects, which were organized into the following five panels:

- Future and Challenges of Humanitarian Interventions

- Global Responsibility – Just a Construct?

- Concept and Practice of Humanitarian Intervention(s)

- Whose Responsibility – Whose Protection?

- R2P and Humanitarian Intervention – Outdated Concepts?

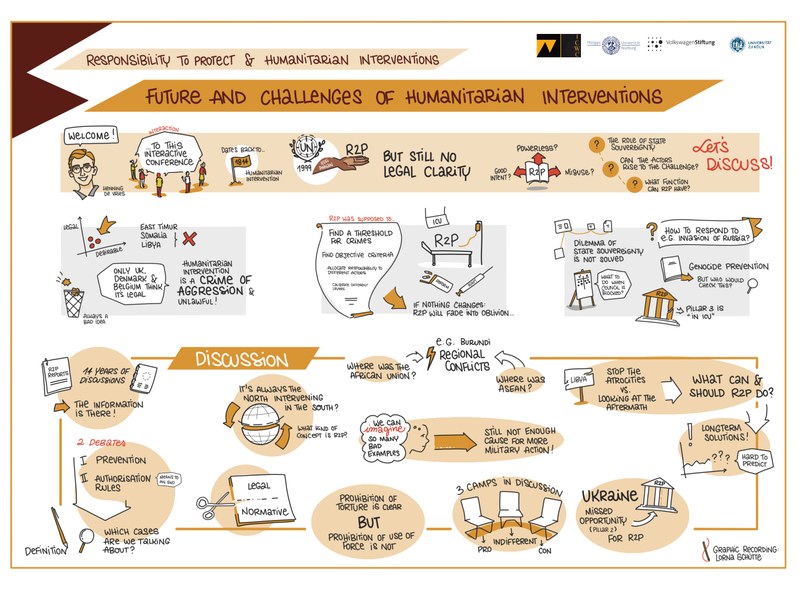

Panel 1: Future and Challenges of Humanitarian Interventions

Panel 1, “Future and Challenges of Humanitarian Interventions,” focused on the future and challenges of humanitarian interventions. It began with a fishbowl discussion, moderated by Dr. Henning de Vries, featuring Prof. Dr. Kevin Jon Heller (Copenhagen), Prof. Dr. Martin Mennecke (Odense), and Prof. Dr. John-Mark Iyi (Cape Town).

Dr. de Vries began with a brief thematic introduction to the status quo and history of military interventions to illustrate various challenges, highlighting both political and colonial motives. He also presented the concept of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) and its three pillars: Prevent, React, and Rebuild. The scientific and political debates surrounding R2P were outlined, with, among other examples, Russia’s justifications for its war of aggression against Ukraine cited as a negative example of using R2P as a pretext for war.

The fishbowl discussion began with an input from Heller. He raised the question of whether humanitarian interventions have a future and answered in the negative, regardless of whether they are legal or practically desirable. Heller emphasized that history has shown interventions to provide only short-term solutions. He concluded that humanitarian interventions are always a poor option and are generally unlawful.

The next contribution came from Mennecke, who disagreed with many of Heller’s points and strongly defended the concept of R2P. He emphasized that it is not so much the concept itself or the criteria of R2P that are problematic, but rather that it suffers from misuse by countries such as Russia. A key question, he argued, is how to respond appropriately to such misuse. Mennecke advocated for a debate on the specific objectives that interventions should achieve and how they could be implemented, including a discussion of relevant authorization rules. He also suggested discussing individual cases in which R2P or humanitarian interventions have already been carried out.

Finally, in his contribution, Iyi called for moving away from the idea of humanitarian intervention and emphasized that R2P should provide objective criteria for assessing precarious situations, develop a framework for various actors, and calibrate the different levels of response. He also pointed out that there is uncertainty about what R2P is actually meant to achieve. Iyi stressed that the future of R2P depends on several factors, particularly a potential reform of the decision-making rules for interventions, possibly involving the UN General Assembly. In his input, he also made clear that attempts are already being made to adapt R2P, but so far these efforts have not succeeded.

The controversial inputs of the panelists were followed by a fruitful discussion with the plenary, which took up the points raised and examined them critically.

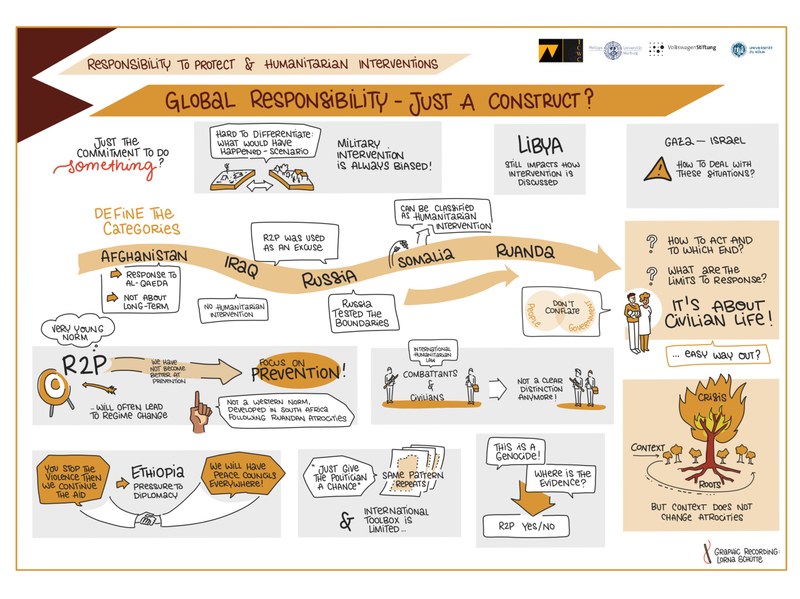

Panel 2: Global Responsibility – Just a Construct?

The second panel, “Global Responsibility – Just a Construct?”, opened with a keynote lecture by Savita Pawnday, Executive Director of the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. She began her contribution with an excursus on the current state of international humanitarian law, using the Israel-Gaza conflict as an example. In her view, this conflict revealed grave violations of international humanitarian law by Israel—an assertion that immediately provoked objections from the audience. To address the question of whether R2P is merely a construct or rather a practical tool for safeguarding human rights, she argued, one must examine whether the international community is truly willing to commit itself to humanitarian interventions.

Next, Pawnday explained that survivors and victims of atrocities or war crimes are generally more positively disposed toward R2P and the use of force to protect human rights. From this, she derived her definition of R2P: it is the use of force for the protection of human rights. She emphasized that R2P still lives in the shadow of the 2011 Libya intervention, raising the question of whether it can still fulfill its original purpose. She pointed out that in public perception, the consequences of humanitarian military interventions often outweigh the intervention itself—particularly when peacekeeping forces become part of the conflict and remain deployed in the region for an extended period. Furthermore, she noted that Western states often ignore the successes of R2P and humanitarian interventions in the Global South, for example in the conflict between India and Pakistan. At the same time, countries such as India and Pakistan tend to interpret humanitarian interventions as “interventions for self-defense.” Looking ahead, Pawnday argued, the goal must be to find new ways to prevent mass atrocities, since current options do not always pursue the objective of prevention. Moreover, it is crucial not to lose sight of the core aim of R2P: the protection of specific populations.

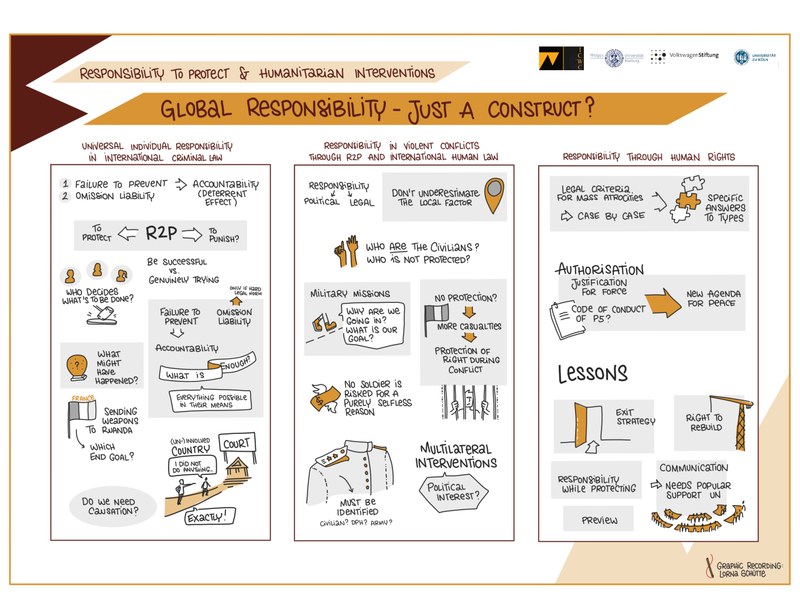

Following the keynote lecture, the conference participants divided into three groups to discuss the following concepts of responsibility: “Universal Individual Responsibility in International Criminal Law,” “Responsibility in Violent Conflicts through R2P and Humanitarian Law,” and “Responsibility through Human Rights.”

Watch the keynote lecture by Savita Pawnday on YouTube here..

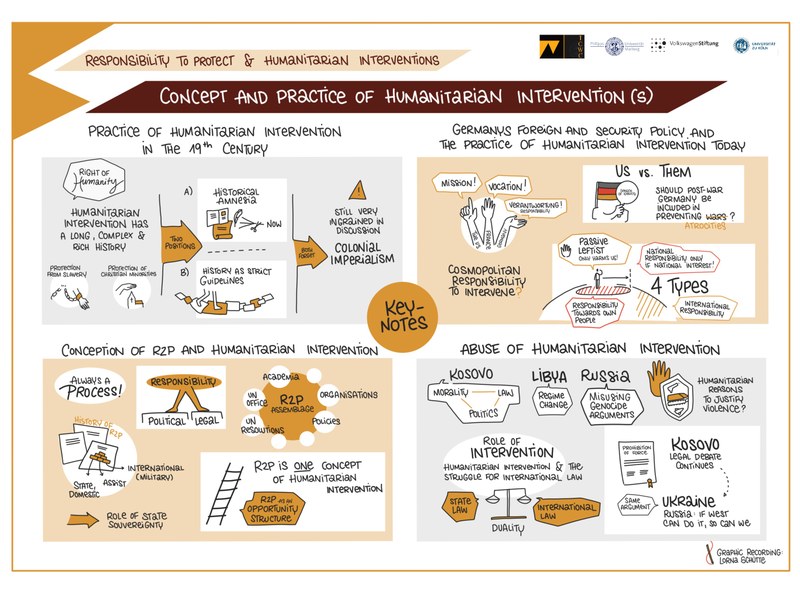

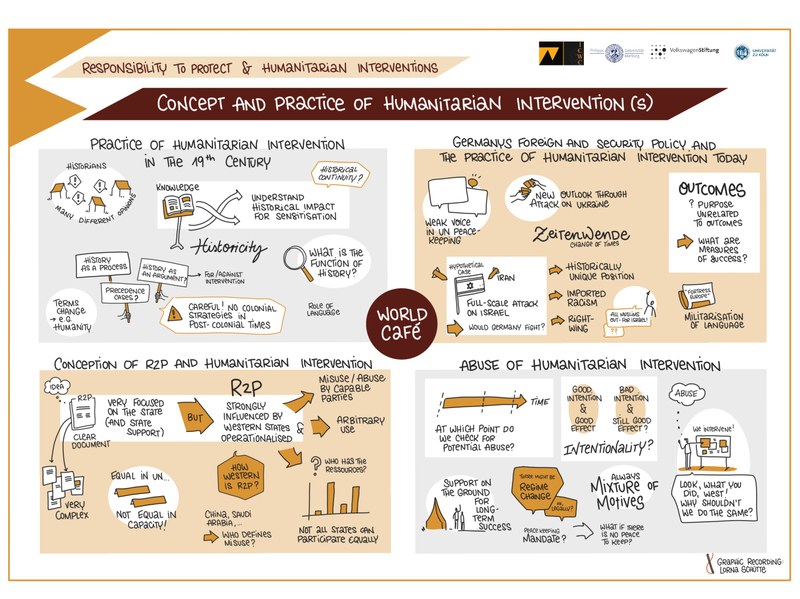

Panel 3: Concept and Practice of Humanitarian Intervention(s)

Panel 3, “Concept and Practice of Humanitarian Intervention(s),” began with four keynote presentations by Prof. Dr. Fabian Klose (Cologne), Prof. Dr. Hubert Zimmermann (Marburg), Dr. Werner Distler (Groningen), and Dr. des. Hendrik Simon (PRIF), each highlighting different aspects of the concept and practice of humanitarian interventions.

Klose spoke about historical perspectives on humanitarian interventions. He noted that such interventions already occurred in the 19th century, but their justifications were largely limited to enforcing the abolition of slavery and protecting religious minorities. He further described the period between the Peace of Westphalia and the Holocaust as a time of indifference, during which humanitarian interventions were very rare. Klose also highlighted that humanitarian interventions were part of colonialism and imperialism, explaining that actors at the time used such interventions to justify their own wars—for example, the Ottoman Empire. From this line of argument, Klose concluded with a look at the present: states of the Global South should approach the concept and practices of R2P critically due to the colonial legacy.

Zimmermann then discussed German foreign policy regarding humanitarian interventions. He argued that a cosmopolitan responsibility is merely a construct, because as soon as this responsibility calls for action, people generally do not feel accountable—an observation he linked to the reluctance to deploy citizens of one’s own state to crisis regions. He went on to describe the Federal Republic of Germany as a “responsibility republic,” a concept that must be understood in the context of the postwar order following World War II. This concept raises questions about whose responsibility is owed to whom and problematizes the contested narrative of international responsibility, which often presupposes a “we” versus “they.” World War II had fostered an inward-looking identity in Germany, which Zimmermann characterized as a kind of post-traumatic stress resulting from the war. This identity initially made it impossible to send German soldiers abroad, though support through military and humanitarian aid was feasible. During the 1980s and 1990s, Germany became increasingly integrated into the broader international community, assuming responsibilities, for example as a member of the United Nations. In subsequent years, the focus of responsibility shifted toward preventing atrocities rather than preventing war, as had been the case shortly after World War II. Zimmermann also outlined different political positions on humanitarian interventions: supporters from the right-wing spectrum could be described as Defensive Realists of the Western alliance; left-leaning supporters as Liberal Institutionalists or Humanists. Critics from the right could be classified as Ethnic Nationalists or Offensive Realists, while critics from the left as National Pacifists.

Distler then presented the conceptualization of R2P. He fundamentally questioned why we focus on concepts like R2P, arguing that the right to punishment provides the answer. He further discussed the emergence of R2P and its three pillars—Prevent, React, Rebuild—which were developed between 2005 and 2009, based on UN World Summit Resolution A/Res/60/1. Distler went on to explain that the UN has sought to develop a clearer definition of R2P, one that would distinguish it from its perception as a Western concept. He also emphasized that R2P should be viewed as one of several concepts of humanitarian intervention, which does not operate automatically but rather functions as an opportunistic structure. This, he argued, is due to political power interests, as states involved in explicit conflicts decide individually which norms are applicable.

Simon focused his presentation on the abusive use of humanitarian interventions. He began by defining what constitutes abuse: it occurs when an intervention does not aim to protect human rights but is carried out for political reasons. Simon then addressed the relationship between humanitarian interventions and international law, emphasizing that discussions of humanitarian interventions inherently involve debates about international law. He provided both historical and contemporary examples of abuses: the war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire in 1877, during which Russia already misused humanitarian interventions to achieve political goals, and the current Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, citing Russia’s submission to the ICJ in which it invoked humanitarian reasons to justify its attack on Ukraine. In conclusion, Simon stressed that humanitarian interventions have always been used as a pretext to circumvent international law.

Following the presentations, the participants moved to the different stations of a World Café, where the topics and theses presented were discussed in a rotating format under the moderation of the presenters.

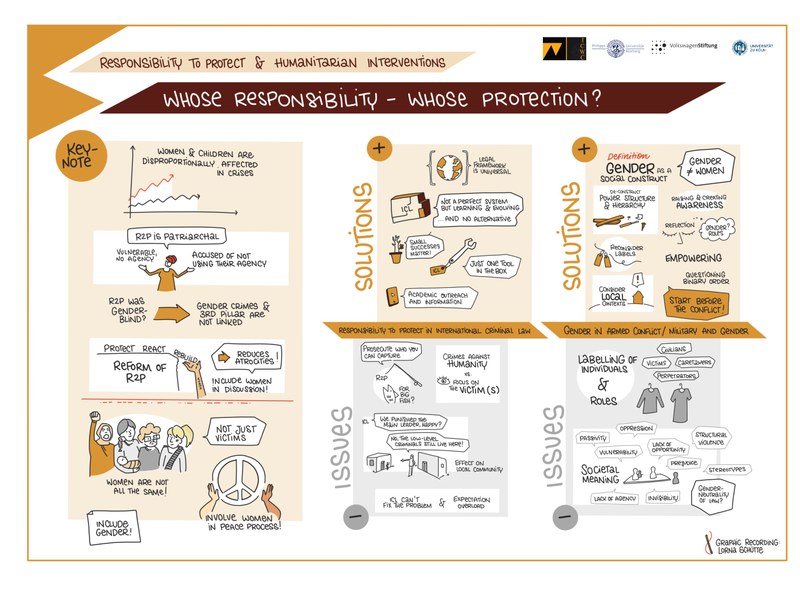

Panel 4: Whose Responsibility – Whose Protection?

Panel 4 was titled “Whose Responsibility – Whose Protection?” and focused on the question of who is actually protected under R2P. The panel examined discriminatory differences and blind spots in military interventions. It began with an introductory lecture by Dr. Noëlle Quénivet (Bristol) and concluded with a negative-positive conference involving all participants.

Quénivet opened her lecture with an explanation of the 2005 UN World Summit, which established the concept of R2P. She then focused on how this concept is applied in the context of gender-based crimes, particularly against women. A key point of her lecture was the connection between R2P and gender-specific crimes. Quénivet cited a 2020 UN report on R2P and women, which highlighted, among other things, that women and children are disproportionately affected by crises falling under R2P. Nevertheless, gender-based violence in pre-conflict situations is often not considered in UN documents as a potential reason for intervention. She also addressed the problem that the “Rebuild” pillar—the third pillar of R2P—is frequently neglected and that women should be far more involved in these processes. There is a discrepancy between the perception of women as vulnerable and their actual capacity to act as active participants in post-conflict societies. Quénivet emphasized that gender role expectations affect both men and women; however, women are often depicted primarily as victims—for example, in the context of sexual violence. The aforementioned 2020 UN report nonetheless recognizes that women are complex actors who can also take on the role of perpetrators. She also highlighted the need for dialogue with those who initiate conflicts—typically men—and noted that women should be more strongly involved in peace processes. In summary, Quénivet called for greater consideration of gender issues within the R2P framework, as well as more active participation of women throughout the post-conflict reconstruction process to prevent further discrimination and promote more effective solutions.

The keynote lecture was followed by a negative-positive conference. For this, the conference participants were divided into two groups, each focusing on a specific topic: Group 1 discussed “R2P in International Criminal Law,” while Group 2 addressed “Gender in Armed Conflict and the Military.” First, both groups collected and discussed specific problems during the negative conference. Then, in the positive conference, each group addressed the other group’s topic and worked out possible solutions to the issues raised.

The first group of the negative-positive conference, “Responsibility to Protect in International Criminal Law,” was moderated by Prof. Dr. Stefanie Bock (Marburg). During the negative conference, it was noted that international criminal law and the R2P concept face similar problems and are predominantly Western-oriented concepts. It was also observed that differing cultural backgrounds lead to varying values and expectations of these systems. The question of who decides whether the national level is doing enough for prosecution was also raised. Additionally, the selectivity of international criminal law and R2P, as well as their political motivations, were discussed. It was emphasized that international criminal law cannot act preventively, may neglect the actual perpetrators, and does not always provide sufficient justice for the victims.

In the positive conference, it was emphasized that there is no alternative to international criminal law and that, despite its imperfections, it should be used as effectively as possible. The group concluded that international criminal law is still a young system, offers room for improvement, and is only one tool in the toolbox, and therefore should not be overburdened. Furthermore, it was discussed that expectations of international criminal law should remain realistic, and that the academic task is to inform the world about international criminal law and its possibilities.

The second group of the negative-positive conference, “Gender in Armed Conflict and the Military,” led by Quénivet (Bristol), Major Dr. Friederike Hartung (ZMSBw), and Linn-Sophie Löber (Marburg), addressed the negative and positive aspects related to gender in armed conflicts. During the negative conference, the definition of gender was clarified as referring to social and cultural norms. Challenges such as the conflation of gender with women, the binary understanding of male and female, and the organizational structures of states and institutions were also highlighted.

In the positive conference, raising awareness of these issues, deconstructing power structures, regular reflection, questioning gender stereotypes and established norms, and taking local contexts into account were highlighted as ways forward. Additionally, a reevaluation of labels was called for.

You can watch the keynote lecture by Dr. Noëlle Quénivet here (YouTube).

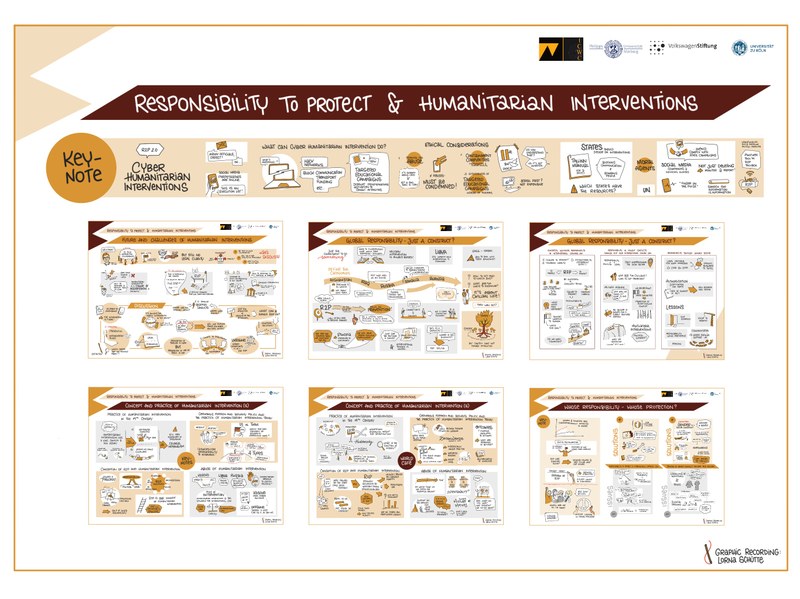

Panel 5: R2P and Humanitarian Intervention – Outdated Concepts?

In the final panel of the symposium, “R2P and Humanitarian Interventions – Outdated Concepts?”, Dr. Rhiannon Neilsen (Stanford) explored a potential future of R2P that could rely more on electronic means of warfare rather than deploying soldiers and using conventional weapons. She explained that the U.S. has already hacked the electronic infrastructure of its adversaries multiple times—for example, the personal accounts of Slobodan Milošević, the network of the Iraqi military, and online accounts of ISIS members. Cyber Humanitarian Interventions are intended to disrupt the commission of atrocities by disabling communication systems, transportation networks, or logistical supply chains. Neilsen also noted that the motivation to commit mass atrocities could be reduced by spreading alternative information, as perpetrators are often active in online forums where they can be reached effectively. She highlighted several advantages of Cyber Humanitarian Interventions: the methods produce fewer “collateral damages,” are cost-effective because no troops need to be deployed, and represent a proportional and reversible means of conducting humanitarian interventions. Furthermore, Neilsen argued that such interventions could increase the political will to act and improve the implementability of R2P. Action should only be taken if the scale and effects are equivalent to kinetic attacks (Tallinn Manual). Even if Cyber Humanitarian Interventions are misused, Neilsen emphasized that their consequences are minimal compared to traditional interventions. Neilsen also discussed the potential actors in a Cyber Humanitarian Intervention: states, acting unilaterally, in coalitions, or under the UN framework. Their task would be to design and regulate these interventions. Additionally, Big Tech companies such as Google or Meta bear significant responsibility regarding the use and release of datasets relevant to Cyber Humanitarian Interventions.

In conclusion, de Vries recapped the symposium using a specially created graphic recording and emphasized that the perspectives discussed on R2P and humanitarian interventions are highly topical, yet receive little attention in (German-speaking) academia. He noted that further cooperation and events on this subject are therefore advisable and forward-looking.

Graphic Recording

The entire symposium was accompanied by a graphic recording. You can view the results here.

The entire symposium was also broadcast live via Instagram (@icwc_mr). There, in addition to an interview with Dr. Rhiannon Neilsen about her lecture, you can find several summary reflections from selected participants. You can access the posts here without needing to register.